Chielozona Eze has written a book of poems that connect the wars of his childhood with the wars of his exile. He goes home to his ancestral land in Nigeria where the Nigerian civil war, his first conventional war began, and in verse he looks at his world inside out. It is a fascinating look, this little book with the enigmatic title, Prayers to Survive Wars that Last. These poems remind us that there are many types of wars, but people mostly think of conventional wars where guns are the bayonets to the heart. Similarly exile is more than a trip to Babylon, once you leave your hearth, the heart knows and grieves for the warm comfort of home, familiar surroundings tastes and smells. Well, most times. Sometimes, you just walk away, never look back, grit your teeth and bite hard into the peaches of Babylon. Life, as war goes on.

Born in 1962, Eze was a child during the Nigerian civil war, a terrified witness to a daily hell. The war remains one of the most written about – and most unexamined of Nigeria’s traumas. That war that raged from 1967 to 1970 consumed over a million lives, mostly Igbo citizens, a genocide that destroyed lives and trust among the major ethnic groups. The timing of the release of the poetry collection is interesting, coming at a time when there is a renewed clamor for, if not an independent Biafran nation for the Igbo, a restructured Nigeria with power devolving away from the center to regions, designed perhaps along ethnic lines.

Born in 1962, Eze was a child during the Nigerian civil war, a terrified witness to a daily hell. The war remains one of the most written about – and most unexamined of Nigeria’s traumas. That war that raged from 1967 to 1970 consumed over a million lives, mostly Igbo citizens, a genocide that destroyed lives and trust among the major ethnic groups. The timing of the release of the poetry collection is interesting, coming at a time when there is a renewed clamor for, if not an independent Biafran nation for the Igbo, a restructured Nigeria with power devolving away from the center to regions, designed perhaps along ethnic lines.

Eze’s volume of poetry has about 47 poems in it, anchored by an interesting essay- preface by the writer Chris Abani. Abani’s essay, by the way. is remarkable more for its claims and assertions than for its substance. When Abani charges, for instance, that “most Nigerian poets focus on the rallying call of protest, politics, and nation,” one senses that he has not been reading a whole lot of contemporary Nigerian poets. Indeed, it is the case that this is one area where African literature is veering away from the monotony and narrow range of poverty porn, grime and protest literature. I am thinking of young and exciting writers like Jumoke Verissimo, Saddiq M. Dzukogi, David Ishaya Osu, Romeo Oriogun, Timothy Ogene, etc, who clearly do not suffer the burden that Abani talks of. As an aside, Abani was born in 1966 on the eve of the war; his claims of being a witness to that war go beyond appropriating someone else’s pain, and comment eloquently on the class distinctions during the war that made the witnessing to fall disproportionately on the voiceless poor. This is where Eze comes in, a child who witnessed and suffered a war he did not ask for. Finally, Abani anointing Eze in this preface as “a true and worthy successor of Christopher Okigbo” is patronizing beyond the telling of it. Eze is his own voice and there are no comparisons. Eze is no Okigbo.

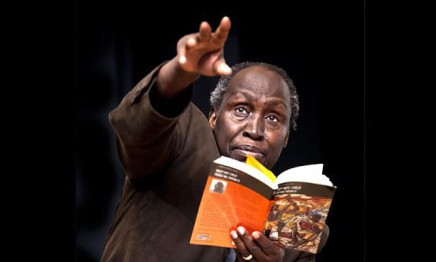

So, who is Chielozona Eze? Google him, and you will get impressive blurbs like this one:

“Chielozona Eze is a Nigerian poet and philosopher and literary scholar. He is associate professor of Anglophone African literatures at Northeastern Illinois University, Chicago. He earned his PhD in Philosophy and Literature from Purdue University, where he also obtained an MFA in fiction. He has master’s degrees in Catholic theology and comparative literature. His areas of research include Igbo poetics, African feminisms, globalization and Africana cultures/identities, literature and ethics etc. He is actively collecting and archiving Igbo oral poetry, and he seeks to continue in the tradition of his father, who was a prominent oral poet in Amokwe.”

It is true, Eze is a remarkable scholar and quiet patron of the literary arts in Africa (who has hosted many writers on his blog), a beautiful soul burdened with the gift of deep sensitivities. A highly regarded scholar and prolific poet, Chielozona Eze was shortlisted for the £3,000 Brunel University African Poetry Prize in 2013. He has published his poems in journals like the Maple Tree Literary Supplement, Eclectica, Northeast Review, and Sentinel Poetry Movement. When the history of contemporary digital African literature is written his name will be right in there along with writers like Afam Akeh, Amatoritsero Ede, Sola Osofisan, Molara Wood, etc.

About the poems, I enjoyed reading the collection, there are many poems to like in this slim volume. The first poem is Lagos, Lagos, a poem that reminds one of the homecoming of a nervous warrior – on the wings of prayers and an airplane. Visually, it calls to mind the pretty line in Teju Cole’s Every Day is for the Thief – of a plane which “drops gently and by degrees towards the earth as if progressing down an unseen flight of stairs.”:

Our plane broke through dense clouds

and glided over a sea of rusted roofs

and skyscrapers

and slums

and palaces

and refuse dumps

and people

and people

From that first stanza, Eze, the war survivor returns to his mother’s hearth. From that poem on, the reader feasts on tender verses that plumb Eze’s angst, pain and longing for a certain peace away from the war of the past – and today’s drumbeats for war. The poem, The art of loving what is not perfect brings Eze’s mother to the reader’s consciousness – on the wings of deep words. In Memory: a parable, Eze is a tormented soul, haunted by the past and the realities of the present, a man apprehensive about a future that is right here, ugly and foreboding:

I know a thing about memory:

It is a blind dog left in a distant city,

It finds a home in a shelter, waiting for love.

Months on, chance brings its master around.

At the sound of his voice it jumps and barks

and whines and wags its tail.

Will the master reject it again?

For Eze, memory is a struggle, memory is life in ether borne on the wings of faith and spirituality. He looks at the past frozen in time, as if with the eyes of a traumatized child. It is a struggle, a painful one for which even prayer does not provide a salve. In Ezes’s memories of war, he emotes beautifully and urges us to remember history:

The past, if forgotten pollutes

the village drinking well

Eze is his own voice but some of the poems do hearken in a good way to the industry and craft of the old masters of poetry. Unknown boy soldiers, The exodus offer hints of Kofi Awoonor and Wole Soyinka. The poems are enigmatic, giving the reader tantalizing peeks into Eze’s world view and politics. His politics is an issue: What does he now think of the Nigerian civil war? Starved girl is typical of most of the poems, seemingly accessible, simple words pregnant with meaning and feeling:

The ground is dirt

Grasses are in spots

A white wall darkens

Two children on a wobbly table.

The one faces the camera.

The other stares at the ground.

Her ribs jut out,

her belly balls forth.

Thinning limbs, bloated feet.

Walking must be hell.

If you listen well you can hear me whisper:

Merciful God,

why are we doing this to ourselves?

The poems make the point painfully that the term, “War is hell” is more than a mere cliché. The poems are powerful enough to not require visual imagery. Hear these lines from Remember me:

She makes it out the door.

Her thighs are stockfish.

Her stomach is a sad balloon.

Faith is a constant subject in Eze’s poetry, he rarely questions it, choosing to revel in its mystery. Memory haunts Eze always. You sit in the darkness of your space and all these images of hurt and longing won’t stop drawing themselves on your conscience. It is not all war poetry; it is that and more. Letter to self from a city that survived is perhaps a defiant clap back to a generation baying for war. It is worth the steep price of the book ($15 for the hard copy, $10 for the digital copy). Ode to my refugee shirt is a nice comforting ditty evoking joy from a sad place.

Faith is a constant subject in Eze’s poetry, he rarely questions it, choosing to revel in its mystery. Memory haunts Eze always. You sit in the darkness of your space and all these images of hurt and longing won’t stop drawing themselves on your conscience. It is not all war poetry; it is that and more. Letter to self from a city that survived is perhaps a defiant clap back to a generation baying for war. It is worth the steep price of the book ($15 for the hard copy, $10 for the digital copy). Ode to my refugee shirt is a nice comforting ditty evoking joy from a sad place.

The reader admires Eze’s generosity of spirit; his verses reflect on other people’s suffering and eloquently uses poetic narrative to reflect on the universality of suffering. Without uttering the word, “love”, Eze’s poems reek of love and compassion and one learns that there are beautiful people who come from a place where the words “I love you” live silently in the hearts, eyes, hands and souls of those who truly love each other.

There are many pieces to love in this slim volume, but my favorite is A new planting season (for Chinua Achebe – 1930-2013). This short moving elegy speaks volumes to the profundity of Achebe’s depths:

Before his last breath the elder showed his hands,

palm up. Empty, he said, like the long road ahead.

I’ve planted the seeds my father put in them;

planted them the way my mother taught me.

Look around you and in the old barn.

More seeds, dung, watering cans, machetes,

two sided machetes. What needed to be said

has been said. Everything else is up to you.

One imagines the poet locked up in solitary talking to himself about the personal and communal pain that won’t go away. There is a war going on, there is a war coming; Eze’s poems make his point plaintively, “I saw war, war is hell, never again.” We can only hope.

Prayers to Survive Wars that Last is available on Amazon. Eze is a veteran digital native and the enterprising reader will find some of these poems freely available online, the book is fast becoming an archival medium. It is not a perfect book; there is a sense in which it was a disappointing production. Editorial issues mar the book, there are quite a few beautiful lines marred by editorial issues, quite unforgivable in poetry. Some of the poems read like works in progress, puzzling fillers for a little book of poems, inspiring the question: Why is this a poem? In a few instances, the pieces suffer from too many words where less or none would do just fine. And then there is the shoddy publishing of the book itself by an outfit called Cissus World Press Books (which by the way boasts the quirkiest, non-responsive website I have ever seen). My copy literally dissolved in my hands as the glue holding the pages gave way. Not to worry, I bought a digital copy online. It is a better production. Which is fine by me, the book is dying anyway. My Kindle is happy.

So how did the serial protagonist Judd Ryker do in The Shadow List? I think he and his wife, Jessica Ryker acquitted themselves admirably. It is a busy little book, Judd Ryker, the main character sets out to confront Chinese expansionist ambitions in capturing the world’s energy (crude oil) market. He soon gets side-tracked into other plots that involve Nigeria’s crude oil market (and its corruption) the encroaching Chinese influence in Nigeria, kidnappings, Nigeria’s politics; drama, corruption, the popular or notorious Nigerian “419” scam, Russian gangs, etc. It is a sprawling plot of subplots that somehow trap an army of colorful characters including his wife, CIA agent, Jessica Ryker.

So how did the serial protagonist Judd Ryker do in The Shadow List? I think he and his wife, Jessica Ryker acquitted themselves admirably. It is a busy little book, Judd Ryker, the main character sets out to confront Chinese expansionist ambitions in capturing the world’s energy (crude oil) market. He soon gets side-tracked into other plots that involve Nigeria’s crude oil market (and its corruption) the encroaching Chinese influence in Nigeria, kidnappings, Nigeria’s politics; drama, corruption, the popular or notorious Nigerian “419” scam, Russian gangs, etc. It is a sprawling plot of subplots that somehow trap an army of colorful characters including his wife, CIA agent, Jessica Ryker. Born in 1962, Eze was a child during the Nigerian civil war, a terrified witness to a daily hell. The war remains one of the most written about – and most unexamined of Nigeria’s traumas. That war that raged from 1967 to 1970 consumed over a million lives, mostly Igbo citizens, a genocide that destroyed lives and trust among the major ethnic groups. The timing of the release of the poetry collection is interesting, coming at a time when there is a renewed clamor for, if not an independent Biafran nation for the Igbo, a restructured Nigeria with power devolving away from the center to regions, designed perhaps along ethnic lines.

Born in 1962, Eze was a child during the Nigerian civil war, a terrified witness to a daily hell. The war remains one of the most written about – and most unexamined of Nigeria’s traumas. That war that raged from 1967 to 1970 consumed over a million lives, mostly Igbo citizens, a genocide that destroyed lives and trust among the major ethnic groups. The timing of the release of the poetry collection is interesting, coming at a time when there is a renewed clamor for, if not an independent Biafran nation for the Igbo, a restructured Nigeria with power devolving away from the center to regions, designed perhaps along ethnic lines. Faith is a constant subject in Eze’s poetry, he rarely questions it, choosing to revel in its mystery. Memory haunts Eze always. You sit in the darkness of your space and all these images of hurt and longing won’t stop drawing themselves on your conscience. It is not all war poetry; it is that and more. Letter to self from a city that survived is perhaps a defiant clap back to a generation baying for war. It is worth the steep price of the book ($15 for the hard copy, $10 for the digital copy). Ode to my refugee shirt is a nice comforting ditty evoking joy from a sad place.

Faith is a constant subject in Eze’s poetry, he rarely questions it, choosing to revel in its mystery. Memory haunts Eze always. You sit in the darkness of your space and all these images of hurt and longing won’t stop drawing themselves on your conscience. It is not all war poetry; it is that and more. Letter to self from a city that survived is perhaps a defiant clap back to a generation baying for war. It is worth the steep price of the book ($15 for the hard copy, $10 for the digital copy). Ode to my refugee shirt is a nice comforting ditty evoking joy from a sad place. Let me also say that “African literature” in the 21st century, to the extent that it is only judged through analog books by literary “critics” schooled in the 20th century Achebean era, will always distort our history and stories. I have said that many African writers write poor fiction because they tend to force their anxieties about social conditions into the format of fiction. The result is often awkward, they should be writing essays. But I was primarily thinking about books. Today, the vast proportion of our stories is being written on the Internet by young folks who do not have the resources that the West availed Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o et al in the 60’s. Why are we judging African literature only through books? Why?

Let me also say that “African literature” in the 21st century, to the extent that it is only judged through analog books by literary “critics” schooled in the 20th century Achebean era, will always distort our history and stories. I have said that many African writers write poor fiction because they tend to force their anxieties about social conditions into the format of fiction. The result is often awkward, they should be writing essays. But I was primarily thinking about books. Today, the vast proportion of our stories is being written on the Internet by young folks who do not have the resources that the West availed Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o et al in the 60’s. Why are we judging African literature only through books? Why? Lastly, to imply that Achebe was an ordinary writer is beneath contempt. Literature, stories must not be divorced from their context. Achebe’s generation wrote for my generation of children because no one else would. I would not be here today without them. They were preoccupied with the social conditions at the time, yes, but they tried to do something about them also. Indeed some died fighting for an ideal (Christopher Okigbo for instance). The challenge for today’s writers is to ensure that they are not merely recording and sometimes distorting and exaggerating Africa’s anxieties and dysfunctions for fame and fortune. To blame Achebe for our contemporary writers’ narcissism is disingenuous and silly.

Lastly, to imply that Achebe was an ordinary writer is beneath contempt. Literature, stories must not be divorced from their context. Achebe’s generation wrote for my generation of children because no one else would. I would not be here today without them. They were preoccupied with the social conditions at the time, yes, but they tried to do something about them also. Indeed some died fighting for an ideal (Christopher Okigbo for instance). The challenge for today’s writers is to ensure that they are not merely recording and sometimes distorting and exaggerating Africa’s anxieties and dysfunctions for fame and fortune. To blame Achebe for our contemporary writers’ narcissism is disingenuous and silly.